Five Things I learned from my Autistic Son

By: Maria Thompson Corley – Confluence Daily is your daily news source for women in the know.

My son, Malcolm, was diagnosed with PDD-NOS when he was three. I remember learning, long before I gave motherhood even a glancing thought, that former CFL quarterback Doug Flutie had an autistic son, and wondering how he could possibly handle such a thing. Finding myself in the same position didn’t answer my question, since each autistic person is different. And yet, all parents of autistic children face the same choice: learn to raise your kid, or abdicate responsibility. The latter never crossed my mind.

I should mention that the learning goes both ways. On one hand, I began to research the current wisdom about mitigating or “curing” the symptoms of autism; on the other, Malcolm began to teach me how to grow. My efforts have had limited success, by society’s standards — Mal struggles with complete sentences unless they follow a pattern, and is often unable to respond to “how” and “why” questions. He stims by forming shapes with his hands or making high-pitched noises at sometimes inappropriate times (like in the middle of a concert, which is why I only take him to shows that are very amplified). His instruction of me, however, is effortless, and while still a work in progress, has had far greater success. In no particular order, here are five things I have learned from my autistic son:

Patience

When he was very young, Malcolm was the fastest thing on two feet, but the years (and perhaps the medications I reluctantly added to his care protocol) have slowed him considerably. While he can do a large number of self-care tasks by himself, he rarely seems to see the urgency behind them unless I prompt him. If left on his own, he will do what he needs to do, but on a schedule that has no correlation to my often harried pace, and if I push him too hard, he resists. The thing is, the need to deal with him gently is good for me. I can’t say I’m always calm, but my urging him to do a good job because I know he can seems like a better parenting strategy than yelling that he’s going to be late. Either way, I get better results with honey than vinegar, and have found that the discipline I’ve learned in being forced to adopt this strategy carries over into the way I deal with other people. Most of the time, anyway.

Hugs are the best things ever

Some people on the autism spectrum don’t like to be touched, but Malcolm is the opposite. I can’t explain how it feels to be the recipient of his gentle hand on your cheek, but let me tell you, it’s something special. He also loves a hug — not from just anyone, but if he loves you, you get both arms, wrapped tightly, with a hand either tapping or rubbing your back. Some of his affectionate gestures are more like stimming, such as when he squishes his nose into the side of my face, but even then, he will only do such things if he feels close to you. Mainly, he’s an eighteen year-old who doesn’t care who sees that he loves his family. Those random pda’s could be embarrassing to some, but I instead feel grateful for the oxytocin. Which leads me to:

Do your thing, no matter who sees it

Okay, there are legal limits to this, obviously. I’m referring to the idea of dancing if you feel like it, even if you’re not an expert. Malcolm has participated in line dances in random places, because he knows the steps and heard the song. His latest dance adventure is zumba. An after-school class was advertised, but Malcolm couldn’t wait, so I took him to a class at the gym near my house. Malcolm has been studying tap for three and a half years, so dancing isn’t new, but I wasn’t sure he’d last through an hour of zumba, since it moves pretty quickly. Mal was sometimes half a step behind, but a lot of the time, he was right there, in sync with the class. And even if he wasn’t, he was having the time of his life. He simply doesn’t care if he’s good at it or not — he just wants to do what gave him joy.

I actually learned the lesson about ignoring the opinions of others earlier, and in a different way. Malcolm talks to himself in public. People may look at me and him strangely as we walk along in the grocery store, my son’s arm often linked in mine, while he recites portions of videos he’s seen on the computer or snippets of Disney movies. I interject, sometimes, trying to make it more of a conversation, but that has nothing to do with the people around us. They may think he’s strange, but I don’t care, and he doesn’t seem to, either. I want him to be less in his own head, and more in the world around him, but then again, don’t we all have a movie going on in our heads, at times? That’s what a daydream is, right? I’m trying to train him to watch the movie without speaking the dialog out loud. But until then, people can stare, if they want to. At this point, to be honest, I’m barely aware of them.

Perseverance

I’m rather busy, so an hour at home is preferable, if I can swing it, to an hour at a gym. I didn’t take Mal to zumba because I want to cater to his every whim. I took him because he was driving me crazy.

Autistic people can get fixated. I am very skilled at saying, “no,” but when Malcolm really, really wants something, he won’t give up. So if it’s positive, or at least, no harmful, and not too expensive, he can wear me down. In the meantime, I have a handy bribe to provide relief to my need to be patient — the honey approach is often combined with threatened loss of a reward. Because a mom’s gotta do what a mom’s gotta do.

Still, Malcolm’s focus on his goals inspires me. The things I’m best at are all iffy — music, writing, voiceovers — and they require persistent self-promotion, something I don’t enjoy. But if I want to get paid to do what I love, I need to persevere, just like Malcolm, until the last possible shred of hope is gone.

Never underestimate anyone

There are people who are surprised by the things that Malcolm can do, simply because he doesn’t talk very much and often seems to be in his own world. Mal has shown me that autism is just one facet of who a person is — there are limits involved, but not necessarily as many as one might think.

My son loves to dance, as mentioned, so I always took him to the school dance. I was nervous the first time, but after it went well — he rarely left the floor — I made sure to take him to all of them if I could. He showed an interest in his sister’s tap shoes, so I found a teacher who would work with him until he was ready to be in a class, which is full of other special needs kids but perhaps wouldn’t have been formed otherwise. He loved to play the drums in Rock Band, so I got him instruction in that; now he plays, on occasion, to accompany my church choir. He has a beautiful voice, and since he was always singing in summer camp and his sister’s voice teacher was willing, he started studying. Now he sings in English, Spanish, Latin, French, Italian, and German. I sometimes see him watching Youtube videos in other tongues. No idea if he is picking them up or not, but then again, why not?

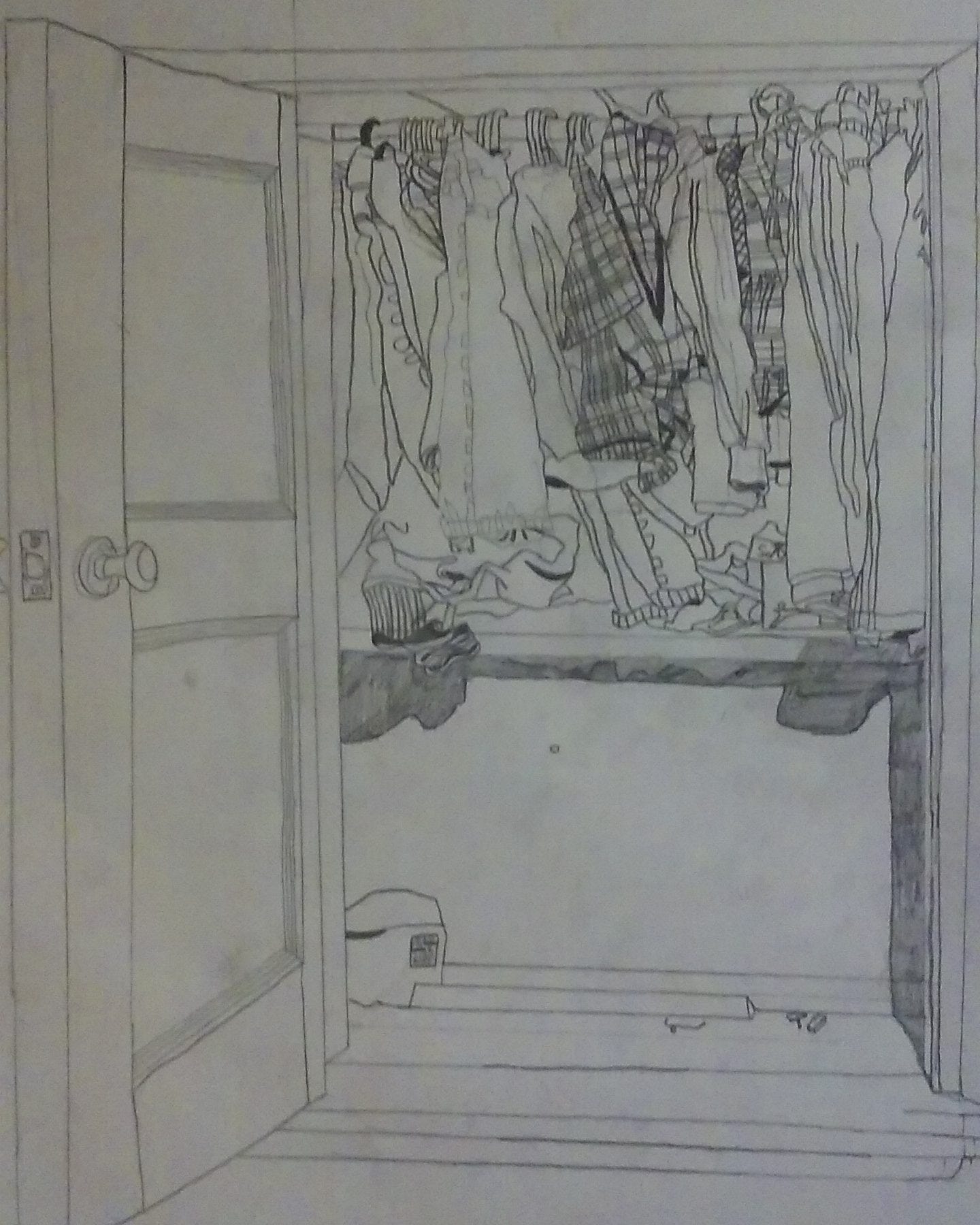

I have no doubt about this: Malcolm is a gifted artist. About two years ago, I started a business for him, Malcolm’s Tiles. I often speak of my lack of entrepreneurial skills, but because of Malcolm, I’ve had to stop underestimating myself. I have a lot to learn in the business realm, but if I’m patient, if I persevere, and if I don’t care if my efforts are sometimes less than top of the line, good things can happen. And if not, I still will have learned something, in the most unlikely way.

There is at least one lesson Malcolm hasn’t managed to teach me: how to cope with the uncertainty involved in having a child with autism, one who relies on me, and who will undoubtedly be around long after I die. But as I continue to grow, I suspect, I will learn this, too. Like everything aspect of my life with Malcolm, it will happen in subtly, with great challenges along the way. And leave me a much better person as a result.

More by Maria:

Maria Thompson Corley is a Canadian pianist (MM, DMA, The Juilliard School) of Jamaican and Bermudian descent, who has experience as a college professor, private piano instructor, composer, arranger and voice actor. She has contributed to Broad Street Review since 2008, and also blogged for Huffington Post. Her first novel, Choices, was published by Kensington. Her latest novel, Letting Go, was published by Createspace, along with a companion CD of solo piano performances by the author. “Malcolm,” a poem about her son which she presented at the 2016 National Autism Conference, is featured periodically on the Scriggler All Stars Twitter page. “Drop Your Mask” was awarded second place in New York Literary Magazine’s love poetry category and appeared in that publication’s AWAKE anthology in December, 2016. Her short story, “The Road to Jericho,” is slated for publication in the inaugural edition of Midnight and Indigo.

Twitter: @MariaCorley